AS: It’s curious that you would have that feeling with the photography, as opposed to making a film and then trying to control how that film goes out into the world. You have much more control over the photographs, how they’re framed, presented, grouped, spaced. Does photography end up feeling static in the context of everything else that’s going on?

MB: I think that’s its value, actually—it crystallizes the narrative in one moment or in one character or one relationship. That was very useful, especially in a system as sprawling as CREMASTER, for example. I think the photography in the CREMASTER Cycle is very useful in that way.

AS: I find the photo suites in Drawing Restraint 9 map a plot sequence that would otherwise be more fleeting—they ground the project.

In regard to the title of the sculpture at McCaffrey, vitrines and cabinets feature strongly in your sculptural language; could you speak specifically to The Cabinet of Nisshin Maru?

MB: For several projects, I’ve made what I called “character vitrines,” which distill elements from the narratives. These vitrines serve both as portraits of certain characters in the films and also to create a connection between character and place. The Cabinet of Nisshin Maru functions as a character vitrine for DRAWING RESTRAINT 9, which is particularly fitting, as the ship was both site and character.

AS: The latest film REDOUBT has strong ties to DRAWING RESTRAINT, but is also a stand-alone endeavor. Do you think that the Drawing Restraint projects will become more autonomous?

MB: Not necessarily. I feel at this point there’s a broader range of possibilities. The Drawing Restraints that were made during the RIVER OF FUNDAMENT exhibition tour (*2), for example, were quite direct. A group of women dragged and pushed a block of graphite through the galleries and made a kind of hemisphere line around the surrounding walls of the exhibition, and it was nothing more than that, really.

AS: And very much in the language of the earlier Drawing Restraints, a residual mark noting a private action.

MB: You know, it took some time for me to get to the point where I felt I could make a Drawing Restraint that I wasn’t involved in as a character. Those works were a hybrid of sorts, and moving forward, the series will continue to pull on the range of possibilities of the different types of Drawing Restraints I’ve made.

AS: It’s interesting to think about that in the context of the exhibition at Fergus McCaffrey in Tokyo, looking at Carolee Schneemann, Min Tanaka and Kazuo Shiraga—their bodies are literally in the work. How familiar are you with the other artists in the show?

MB: Certainly more so with Schneemann, and to a lesser extent Tanaka.

AS: Had you seen footage of Milford Graves’ collaboration with Min Tanaka in Japan?

MB: No, not until Jake Meginsky’s documentary (*3)—it is tremendous, very beautiful.

The Butoh language had been present for me in a general way when I was making the silent out-of-body work in the early ’90s, and although my sources and the tone of the work were much more to do with athleticism and the language of broadcast sports, Butoh was an important touching point in terms of the way the body was being presented—particularly in the Jim OTTO works.

AS: When did you see Butoh performances?

MB: I saw a live work when I first moved to New York, at PS 122, which was certainly however many generations separated from the original gesture. I was also looking at photographs of things that existed in real-time form. So yeah, I would say my relationship to Butoh during that time was as a generalist at best.

AS: In 2006, renowned dancer/choreographer William T. Forsythe described you as a “superior choreographer in every sense” (*4). How do you feel about being called a choreographer?

MB: I’ve always felt there was a strong relationship to dance in the work I was making, and I think it has to do with the way that the narratives depend so much on the relationship between the body and gravity and movement, and for the most part function without text. I feel the overlap has always been natural in terms of working with dancers, directing dancers, and speaking with choreographers—there’s a strong crossover there. My first ventures into working specifically with dancers were really about the mass ornament forms of the 1930s musical—the Rockettes (CREMASTER 1, 1995)—which is really a different kind of thing. But working with those performers felt so familiar to me in terms of the way of one who has a relationship to the body as a tool. There’s a kind of ease I find when working with dancers in terms of directing them, in that I have a similar relationship to my own body that they have with their bodies—it immediately makes the conversation much easier. I still find it quite challenging to work with actors who are looking for a different kind of motivation than a dancer is.

AS: Is the development of that kind of direction an elaboration on athletic routines and systems? Are they one and the same? There doesn’t seem to be a hierarchy in terms of how you talk to a dancer, or direct professional fighters, or organize musicians to move in a particular order to affect sound—

MB: —all of that is choreography, for sure.

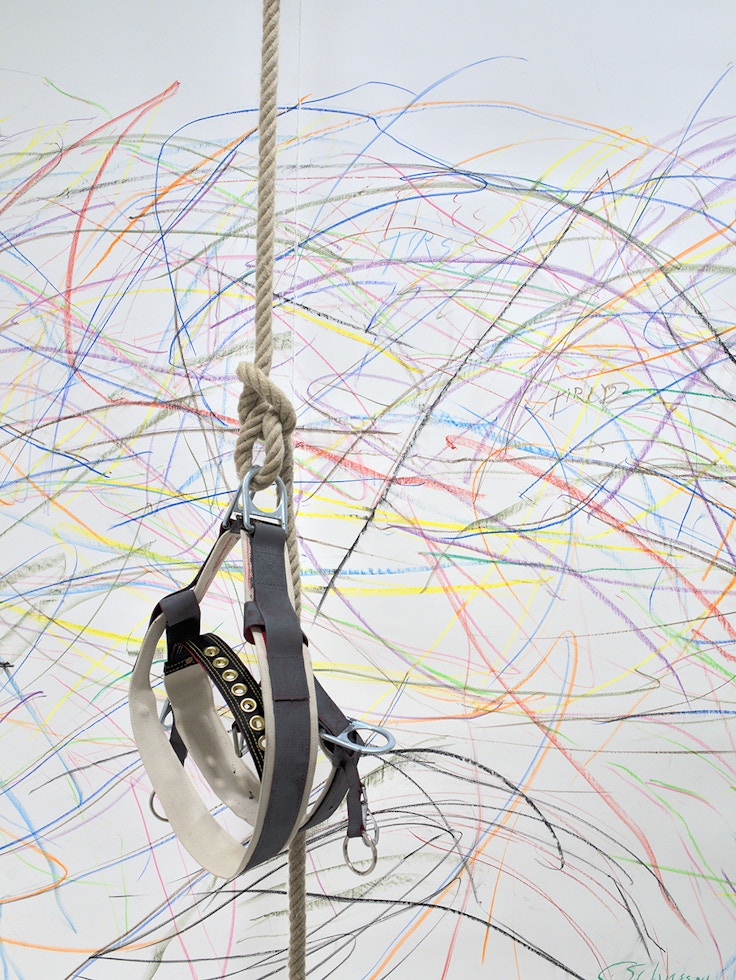

AS: When you saw the Kazuo Shiraga painting in the exhibition at McCaffrey in New York, Japan Is America, did you pick up on his body in that painting? Do you see him suspending himself from a rope? Does it matter?

MB: It does matter, of course. I think intention always matters. The answer is yes, you feel it in the gesture and the speed and the weight.

AS: He did perform sometimes in front of an audience, for example with Challenging Mud (1955). Obviously, there’s a difference between that and how it feels to capture a private action and present it afterwards. For Carolee Schneemann, of course, it was very different—all of those drawing variants were in public with the exception of the one in the McCaffrey exhibition, her last, which she made privately in her in her studio.

Could you talk about the difference between a public performance and filmed private action? Why film the Drawing Restraints privately?

MB: I’ve always had an interest in creating a point of view. The first Drawing Restraints that use the language of athletics and sports broadcast were performed in real time and edited. They were performed with the intention of creating a mediated experience through video. It was always important to me—and not just as a way of carrying forward an artistic practice and having something to show for it. It was the beginning of this way of thinking about a mediated experience and how that functions in sports, how that functions in the body performance that I was exposed to as a young artist and building out from there.

AS: So in terms of the Drawing Restraints—essentially that’s what they are, action and broadcast film, as opposed to, for example, Schneemann’s performance and artifact drawing. Do you want to speak to the parallels between your work and Schneemann’s?

MB: The piece that was really influential for me is Interior Scroll(1975), and I think, like Butoh, it was a way of understanding how the body could be used in performance, but more importantly how that could become narrative. Most time-based examples I think of from that period are not narrative—they tend to be, you know, like Chris Burden’s work, or [Bruce] Nauman. The idea of a text being pulled out from an interior place was very powerful for me in that way. At the time I encountered that piece, I was definitely interested in telling stories and trying to figure out a way to merge my interest in object making and bringing my body as an athletic body into sculpture-making practice.

AS: When is the Hayward Gallery exhibition(*5) set to open, now that it was postponed from 2020 due to COVID?

MB: We’re scheduled to open in May.

AS: REDOUBT was screened in Japan once. Are we going get to see the film tour here?

MB: Up to this point I have presented all of my films in Tokyo, and I’d like to believe we can show this one there too. We’ve been waiting for the possibility to show it on a big screen, without the restrictions that everybody’s dealing with now, so we’re just trying to be patient.