──プロジェクトとしての「拘束のドローイング」は、1980年代後半に基本的な制限を設けるところから始まりました。身体の動きを物理的に拘束するよう設計された空間の中で痕跡を残そうとするドローイングは、かなり早い段階から物語性を見せ、そこから彫刻、写真、脚本ありの映画と、表現方法も広がっていきました。そのなかでももっとも野心的な作品が、2005年に長崎湾で撮影された『拘束のドローイング9』です。同作をフルキャスト、スタッフすべて日本で長編映画として制作することになったきっかけについて教えてください。

その頃、日本で展覧会をする話をいただいて、金沢付近を旅しながら、何をしようかと考えていました。「拘束のドローイング」の新作を作ろうというアイデアが生まれたのは、金沢21世紀美術館での個展をキュレーションしていた長谷川祐子さんと、これまでの同シリーズを網羅する展覧会にしようと話をしていたときです。「拘束のドローイング」についての展覧会をやろうという話と、日本で新しい「拘束のドローイング」をつくろうという話のどちらが先に始まったのか、正直よく覚えていません。その頃ブラジルで『DE LAMA LAMINA』を完成させたばかりだったので、自分とはあまり直接関係のない、自分のものではない文化のなかで制作をするときに直面する似たような問題に、また向き合うことになるなという気がしていました。

──長谷川祐子さんからのお誘いがあるまでは、特別日本でつくりたいと考えていたわけではないんですね。

そうですね、ブラジルも同じように招待があってのことでした。ミュージシャンのアート・リンゼイが何年も前から「カーニバルに来いよ、絶対来なくちゃ、何か一緒にやろう」と言っていたので、それが実現したんです。そういう意味では状況は似ていると思います。

──つまり南米でも日本でも、手探りで前に進みながら特定の状況を提示しなければならないということですか? プロジェクトを進めるうえでの制限や試練が似ていると?

ええ、とくに当時の制作方法は、場によって、サイトスペシフィックな文脈から物語に向かって作業を進めていくというやり方が多かったので。日本でそのように作品をつくるのは、制作の面でも、文化的な面でも、あらゆる段階でかなり難しいと感じました。例えば『クレマスター』では、自分の出身地でなくても西洋の感覚は共有できたので、比較的簡単に、いわゆる個人的な経験に引き寄せて作品をつくることができたんです。

──『クレマスター』では、まだ物語を監督しているというか、ストーリーそして映画そのものを自らがコントロールしていますね。『拘束のドローイング9』では、他者の文化に身を浸しながら自分の美的言語をそこに調和させていく複雑さのなかで、あなた自身のストーリーはどこにあるのでしょうか?

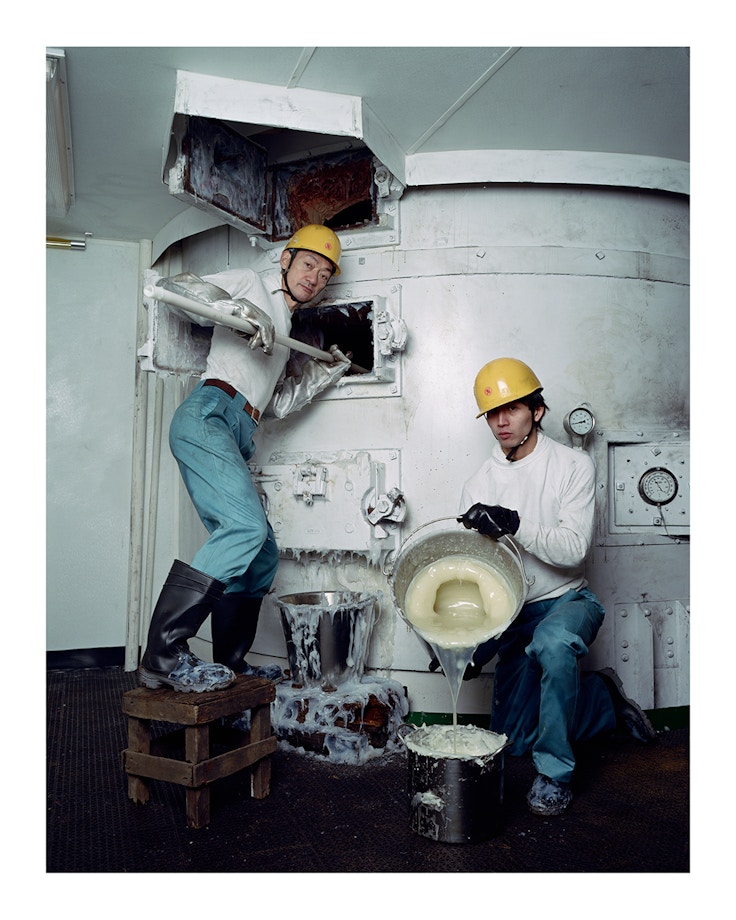

『拘束のドローイング9』の直前に、ブリクストン(ロンドン)の映画館「リッツィー・シネマ」を占拠するようなことをしました。映画館のロビーで5トンのワセリンを鋳造したんです。造形は自重で崩れることを想定してやったのですが、そのような規模で計算するのは難しく、結果文字通りロビーを消滅させてしまいました。本当に自重を支えることができなくて、型を外した途端に映画館の壁から壁へとワセリンが広がってしまったんです。結局、映画を観てもらうときは別の入り口から映画館に入ってもらわなければならなくなりました。これはある意味インスタレーションとしては失敗だったのですが、とても面白かった。物質的な問題としてはとても刺激的でした。

日本を旅していたときもそのことが頭にあり、捕鯨産業について調べながら捕鯨船員たちが直面している物質的な問題に興味を持つにつれ、その二つを合わせて考えるようになりました。解体用の甲板に乗るクジラの体は、一旦皮を剥いでしまうと、大きな重量を持った塊──脂肪に向き合わなければなりません。そのため、クジラの体を海上で処理する工船には、処理に必要なすべての機器が甲板に設置されています。これが『拘束のドローイング9』の最初の条件となりました──海上に浮かぶ船の解体用甲板で巨大なワセリンを鋳造して、船上の捕鯨機器を使ってその物質を処理するのです。

──日新丸から許可を得る手続きはかなり難しそうですね。どうやったのですか?

長谷川祐子さんと一緒に何度も打ち合わせに行って、捕鯨協会から何度も断られて、それでも毎回少し違う角度からプレゼンし続けていたら、突然道が開けたんです。今振り返ってみると、許可が下りたのは本当に驚きでした。おそらく1年半くらいかかったと思いますが、制作以前の準備をあまりにもこのようなお役所手続きに費やしていて、映画に影響が出始めているのではと思ったのを覚えています。当時はかなり焦燥感にかられましたが、最終的には本当にねばって良かったです。

──話をブリクストンに戻しますね。コントロール不能な彫刻で映画館へのアクセスを妨害することと、日新丸で起きていることには類似性があると思うのですが。

あのシネマ・インスタレーションは、「クレマスター・サイクル 」シリーズにフォーカスした展覧会の開催中につくられたものです。Artangelとのプロジェクトと併せてロンドンのリッツィー・シネマで映画5本の上映を行うタイミングだったので、まさにシリーズの全貌を発表する機会だったんですが、同時に、「クレマスター・サイクル」の映画にはかなりはっきり物語のなかに存在しているけれども、彫刻作品には不在の「キャラクター」をつくろうとしていたのです。それはエントロピーというキャラクターで、より非物体的な、離型したときに形をとどめない作品をつくりたいと思っていました。「クレマスター」は私にとってそういう働きをする側面があるんですよね。5つの個別の物語に結実しているとはいえ、作品自体はもっと形を持たないものであり、当時はそれを彫刻的に表現することが重要だと感じていました。「クレマスター・サイクル」展が巡回するなかで、彫刻がいわゆる「登場人物」の役割を果たすのを見て、何かが欠けているような気がしたのです。

──「拘束のドローイング」シリーズは、だんだんと拘束が解けてきていると言えるのかもしれません。初期のアクションには明白な制限が設定されていたのに対して、その後はマルチメディア、マルチな場所、マルチな状況での物語へと発展しています。これはシリーズのなかで起こっていることを反映してのことなのでしょうか?

まあ、《拘束のドローイング7》(1993)は、明らかに重要な分岐点だったと思います。拘束のドローイング的言語のなかで、より物語的で他の俳優を巻き込んだ作品をつくることを試みたので。拘束された状況や拘束の条件のなかで痕跡を残そうとすることと直接的につながっているものではありません。それをもっと物語的に、より心理学的な一連の問いを通して実行しようとしたのです。そういう意味では『拘束のドローイング9』もまた、『クレマスター』で培った映画制作の言語を応用しようという試みでした。「拘束のドローイング」が長編映画として成立するのか、知りたかったのです。

──制作中は、今後の「拘束のドローイング」シリーズの展開についても考えているのですか? それとも制作中の作品で創造的な思考はいっぱいになっている?

《拘束のドローイング8》はエロティックなドローイングの連作で、それはある部分では『拘束のドローイング9』に続く展開だったと思うのですが、そのときは気づいていませんでした。それが2003年だったので、《拘束のドローイング7》から何年か経っていたということですね。新作をまたつくりたいという気持ちは確かにあったんですが、「拘束のドローイング」展が巡回しているあいだにあれこれやってみるのは長編映画が完成してからにしようと思っていました。

──各展覧会会場でパフォーマンスをするとか、ですよね。金沢、ソウル、サンフランシスコなど......(*1)。

そうです。

──最近『拘束のドローイング9』を改めて鑑賞しました。素晴らしかった。この映画は、それぞれ特徴的でありながらつながりもある日本の様々な儀式を中心に構成されているので、厳格な印象を感じます。食事の準備や、伝統的衣装や、お茶など。私自身の日本での経験のなかでも、それらの儀式が展開されていく様に真の厳しさが宿るように思いました。儀式中心に展開される物語は持続しないので困惑する部分も多いですが、これは概念的に意図されたものなのか、それともこれまで説明していただいたようなプロジェクトの過程で生まれた副産物なのか、どちらでしょう。

日本の文化には、動作や行為が儀式を通してどのように形に吹き込まれるかを示す素晴らしい例がたくさんありますし、信念もまた、形に吹き込まれていきます。非常に興味深いですよね。私はつねに物語を形に落とし込む方法を模索してきて、儀式化された動作はそれをするに有用な方法であることが多いので、長年この手法を使っています。しかし、物語や場に対する私の基本的な向き合い方としては、これらは作品のための一時的な状態であり、作品をある種のゲストとして考えるなら、ゲストにはホストとなる身体が必要で、それらは一時的な関係にあるというスタンスです。作品は発展する必要があるので、次の新しい地点、新しい物語、新しい場を見つける必要があります。ですから『拘束のドローイング9』はいろんな意味でそういった状態、関係性の一時的な性質についてのものなのです。

──映画のクライマックスで、二人の招待客がクジラに変身して海に放たれていくような感じですね。では、動作を形に落とし込んで、その形をどのようにとらえるかに応えるのであれば、過去にその動作をどのように記録したかによって動作が決まるのでしょうか?

経験を積むと人は経済的になると思います。いま、映像の仕事を開始するときは、写真的に何が必要なのかわかったうえで始めます。例えばセットやシチュエーションをつくるときには、カメラがどこに置かれるかを一緒に考えます。若い頃は違って、セットを丸ごとつくり、空間全体をつくってからカメラをどこに置くか決めていました。以前は、いまのように考えるための経験がなかったんです。

──写真作品を制作することは少なくなってきていますね。その変化はいつ頃からですか?

一番簡単に説明するなら、彫刻や映像、ドローイング、パフォーマンスなどの形態はすべて、似たような作用を持って発展、存在しているように感じました。それ自体が世界に抵抗するような性質を持っていて、できあがる内容はある種それがどうやってつくられたかというプロセスに依拠しています。写真については、そのように感じたことがないのです。写真としては、それを他の形態から盗まれたように感じたと思います。だから、私にとってとても重要なものだと感じることもありましたが、写真との関係についてはいつも悩んでいました。簡単に撮れてしまうことに憤りさえ感じていました。

──映画をつくって、その映画がどのように世界に出ていくかをコントロールしようとするのとは対照的に、写真にそのような感覚を持つのは面白いですね。写真のほうがどんな額に入れるか、どのように展示するか、どの写真と一緒に見せるか、どのような配置にするかなど、コントロールしやすいと思いますが。写真は、周りであらゆることが起こるなかで、静止した感じに見えてしまうのでしょうか?

それがまさに写真の価値だと思います。物語をある瞬間、あるキャラクターやある関係性のなかに結晶化させること。それは例えば、『クレマスター』のように際限なく広がる体系のなかではとくに有用でした。「クレマスター・サイクル」シリーズにおける写真は、その点において非常に効果的だと思います。

──《拘束のドローイング9》の一連の写真も、写真になっていなければ見逃してしまいそうなほんの一瞬をとらえていて、映画の筋立てやプロジェクトの輪郭をはっきりさせていますね。ファーガス・マカフリーギャラリーで展示中の彫刻作品《The Cabinet of Nisshin Maru》のタイトルにもあるように、ガラス棚やキャビネットはあなたの彫刻言語によく登場しますが、この作品についてもう少し教えていただけますか?

いくつかのプロジェクトで、「キャラクター・ガラスケース」と名付けたものをつくりました。ガラスの陳列ケースに入った作品は、映画のなかの特定のキャラクターのポートレートであり、また、キャラクターと場所のつながりをつくり出すものでもあります。《The Cabinet of Nisshin Maru》は『拘束のドローイング9』のキャラクター・ガラスケースとしての役割を果たすものですが、日新丸は場所であると同時にキャラクターでもあるので、とくにふさわしいと思います。